|

|

Destiny takes us down a path that crosses and intermingles with many lives in our lifetime. The military accelerates this process, increasing the complexity and diverse backgrounds with which we come in contact. Most of the time they are an intermittent passing or short duration.

Larry Haupert and Warren Smith started their lives

miles apart but were linked forever by the USMC. The length of service

time spent together and similarity of assignments were remarkable.

|

|

Larry Haupert was born in Huntington, Indiana on October 14, 1942. This joyous occasion was duplicated 2 days later, in Burlington, Vermont with the birth of Warren Smith. Our common paths were 865 miles apart, but due to become closer when my dad accepted a job with Purdue University. Larry and I were now only 100 miles apart and sharing a common background of corn, hogs, and basketball. We didn’t know it at the time, but we were also staged to begin of our tours of duty with the USMC from a common point.

We probably met on May 10, 1960 when we both enlisted in the USMC on a 120-delay program, but remember only what happened to us personally that day. It consisted of many tests and physicals at a common military clearinghouse in Indianapolis. It was a time of excitement with a lingering fear we might fail something and not be allowed to join. I met one individual that had failed the intelligence test for each branch of service in Kentucky and was trying his luck in Indiana. His current attempt was with the USAF and he informed me he was going to be a fighter pilot. He said that once setting his mind to do something he didn’t give up. I believed his determination, but shuttered later when working with USAF planes wondering if he had achieved his second goal. In a few short years, it became a goal for some draftees to work as hard to fail any of the service tests. I showed a high sugar count in my urine and a Marine sergeant told me to go to the water fountain and drink it dry. Once I had been diluted, they would test me again. This advice worked, but he didn’t tell me you couldn’t leave the multi-hour mental and aptitude test that was next. I thought I would explode before I was allowed to use the head. The crowning glory this day came with the swearing in commitment making us feel pretty proud of ourselves. The USMC placed us close together with Larry’s service number 1912026 and mine being 1912029. Our service record books had been started and were going to start looking like duplicate copies.

The summer of 1960 was a strutting summer by being a Marine with your friends without having to earn it with the rest of the Corps. We were already starting to be looked up to by our buddies and young ladies. We walked a little taller with our chests puffed out causing some to walk a little wider birth around us. We let the idea grow with our friends that we must be tough if we were volunteering for the renowned USMC training. Even our parents looked at us with a little more respect thinking we might just make something of ourselves. Marines we knew didn’t say much of our future, but there was a hint of a smile on their lips.

My future was already taking shape with the USMC. The water pressure apparently didn’t flood my brain as the recruiter said my test results were high enough for him to recommend “Guaranteed Aviation”. Aviation or not; all I wanted was to be a Marine. Larry was also on the same track. We would find out 120 days later that some of our drill instructors thought being in Marine aviation was cheating the title of Marine. It is not good to be “special” in boot camp.

All of the 120-day wonders of our group boarded buses in various Indiana towns and cities on the morning of September 7, 1960 with a destination of Indianapolis. We had to wait the whole day at the same clearinghouse, while the inductees of that day went through the same tests we had already passed. The day was long, but we were “veterans” for at least a short time.

I was put in charge of some raw recruits, because of my veteran status, with the responsibility of getting them to San Diego. All of a sudden being a “veteran” was not so fun. I had a stack of service record books and a bunch of guys not yet use to taking orders from anyone, especially me. When we got to the old Chicago airport it was nighttime and the bright lights seem to scatter my group to the wonders of the big city. We were to take a non-stop night flight to San Diego on a DC-6 full of soon to be Navy and Marine “boots”. I sweat it down to the last few minutes, but all my charges who I had service jackets showed on time. All aboard were in top spirits and verbal challenges rang between groups as we winged our way west. We hadn’t taken off till after 1:00AM and the day was starting to really get long. Fatigue was setting in and the plane got quieter as most starting to think of what greetings awaited us on the horizon.

MCRD San Diego shared a fence with Convair Aircraft Co. and the city airport. As we taxied by MCRD on our way to the terminal, I looked out at the Quonset huts and it seemed as through everyone was running somewhere. Later when we were picking up paper along this same fence, we would experience a complete isolation. The people walking from the parking lot to their jobs would not look at us or even acknowledge we existed. The stewardess bid us good-by as we left the plane with the statement, “Have a good time boys”. There was something about how she said it that made me want to hold onto my ass. I started to ask myself, “What in hell did you get yourself into”. This was reinforced in the airport restaurant following a call to a phone number given to me in Indianapolis. A voice at the other end said, “hold on to that phone and do not move an inch”. “I want to see it still in your hand when I get there”. I did just as I was told and so did he; he was there in an instant. I handed him the service jackets and he gave me a strange look. He informed me that I had told him I had a certain number of recruits to pick up not service jackets, “where in hell are your recruits”? I told him they were hungry and having breakfast in the restaurant. He said he didn’t care and they better be outside in 2 minutes or he would have my ass. I now knew why all those people were running, I had become one. I didn’t have time for excuses that the meals hadn’t come or they weren’t done yet. I just told them they did not want to piss off the Drill Instructor I had just met. I think we did take a little longer than 2 minutes, but not much. From that point on we were either marching or running everywhere we went. Larry and I were in the same series at MCRD with Larry in Platoon 185 and mine Platoon 187. For the next 12 weeks, we labored under the watchful eyes of our drill instructors as they molded us into the current model of Marines. We shared one of the proudest days of our lives marching together past the reviewing stand to be given the title of U.S. Marine. This was immediately followed with combat training in the same company at Camp Pendleton.

We were at the Infantry Training Regiment over Christmas and the training shuts down during this period. The choice was given to the trainees during this period of either being on mess duty or taking leave; Larry and I went on leave. We were also told that representatives from the Union Pacific would come to the base and give us a special deal on a “holiday train”. Even better, this “holiday train” would pick us up right on base. When the big day came to depart, we mustered out in front of our Quonset huts with the only traveling luggage we had, sea bags. We were told the closest the train could get was just over the hill next to the huts and it was there waiting for us. Larry and I, along with most Midwestern folks, would place this hill in the category of a small mountain. We had been up that “hill” with rifle and pack and it was a killer. The trip over this “hill” in winter dress greens and a sea bag really tested your will to go on leave. From the top of the hill, the scene looked like something out of an old western movie. We could now see “our special train” in the distance on a small spur line between the flats of the Pacific Ocean and foothills. A number of very old Union Pacific cars sat hooked to a single engine idling in the middle of nowhere. It was a perfect train robbery scene. They were the old gondola type cars with marble sinks in the lavatory and fixtures for kerosene lamps on the walls. We dusted ourselves off, stored our sea bags, and started our run to Chicago. It soon became apparent this was not the express run. We had to pull off and let every other train in either direction pass by us. We also seem to be consuming a lot of beer. The price didn’t seem to matter as we had been in the USMC since September with very little to spend our $78/month on. It seemed about every 100 miles our train stopped to restock and also let off passengers. It seemed as if someone lived close to any railroad crossing this train would stop and let you off. When we had discharged a certain number of passengers, the conductor would move all the remaining Marines from the last car forward and cut that car loose from our “troop train”. By the time we got to Chicago, we had cut loose all but 3 cars. We had MPs that were on board with us earning their way home for the holidays. We found that their main job was to keep us on the train and out of the public eye, especially whenever we pulled into a major station. They would position themselves outside the train on the platform and rap on your fingers with nightsticks as you tried to wave to young ladies from the open windows. We were beginning to feel like prisoners and treated as such. There must have been concern that this many fresh out of “boot camp” Marines could create a negative incident if left unchecked. By the 3rd day, we were getting close to Chicago and we could tell it had been a long time since these cars had ventured north. The steam lines for heat and control of the brakes kept freezing up. They would stop the train for hours while maintenance people would be underneath with flares trying to thaw the lines. Inside the train everyone was getting into the sea bags for extra layers. That big old horse blanket great coat you never thought you would wear became a prized item. Everyone kept saying to keep going before we all froze to death. I think their biggest concern was not the continuing forward, but the ability to stop when reaching Union Station in Chicago. I didn’t realize how bad this deal was until returning on the El Capitan from Chicago to Los Angeles. The complete trip was made in just 33 hours with comfortable seats, fine dinning, and no MPs.

Our guaranteed aviation orders were cut for Aviation Maintenance School in Millington, Tenn. following completion of combat training. Larry and I spend 18 weeks training in various classes and graduating in the same helicopter maintenance class with the MOS of 6481. Memphis had been a good duty station with the exception of needing a locker in town for your civilian clothes. We had experienced Beal St., the Cotton Festival, seen Elvis driving around, and found the best part of the cheapest hotel meal was the endless amount of hot rolls and honey. It was amazing how many guys could share a room when the mattresses and innersprings were distributed around the room. I think it prepared us for later carrier duty.

The list of common entries in our service record books continued to grow as we shipped out to HMR(L)-363 located at MCAF Santa Ana, Ca. We would finally start earning our keep as helicopter mechanics at this strange little base with massive blimp hangers set in the middle of orange groves. These hangers were impressive forms on the outside and inside at night they took on a life of their own. The inside structure was all wood beams to cut down on a possible spark that could ignite the hydrogen used in earlier blimps. The building would start to snap and groan as the temperature changed from day to night. Owls lived up in the structure and would swoop down at night to scare the hell out of unsuspecting mechanics. We had been schooled on the H-19 in our maintenance classes and the UH-34 seemed a lot bigger. Larry worked for SSgt. Pavan and I was with SSgt. Shepherd. They became our mentors showing us the how to take care of this bird and the responsibilities of being a crew chief. It was the summer of 1961 and we got to experience carrier qualifications, Camp Pendleton, 29 Palms, and Yuma. We even got to go on some forest fire fighting flights. The title of “Hollywood Marines” was given to Marines that went through “boot camp” in San Diego, but it wasn’t bad at all being close to LA, the beaches, and other great liberty areas. The civilians that lived around the base did not share this good feeling. I remember the first time I was hitchhiking into Santa Ana, a carload of civilians tried to run me into the ditch as they all gave me the finger. Welcome to California.

In 1962, a new squadron was being formed on the base with personnel from all the other squadrons. Its special mission was the upcoming atomic tests at Johnston Island. The squadron would have the task of personnel movement from the island during a test and instrument missile recovery following a blast. We would also be working directly for the Atomic Energy Commission. It sounded like a great adventure. We would be operating out of Hawaii and added to that, both our crew chiefs were going to the new squadron. Larry and I transferred on February 19, 1962 from HMM-363 to HMM-364.

Yellow Gold was our color and it was everywhere to show our pride. We waxed our planes to a high shine and performed our mission with honors. In between watching the terrifying power of atomic bombs explode; we enjoyed the tranquil life of Hawaii for 9 months. It was great to get your plane ready to fly on Ford Island and then go relax by the pool in your swimsuit. We learned to consume all the exotic South Seas drinks at the many bars in and around Pearl Harbor. The sub base was always a good party as most of the participants had been under water for 90 days thinking about busting loose. The air was punctuated with flying beer bottles and there was always had a couple of fights in progress. Even though it was a Navy Club, we always seemed to be welcome. I think the submariners considered themselves a cut above the average sailor. There was no doubt where we stood in this comparison.

Larry and I took leave together between the two atomic test tours in his 1954 VW. Armed with peanut butter and bread from the mess hall, we had spent a total of $15 getting all the way to Elk City, Oklahoma before blowing a timing gear. This little fiber gear is located inside the engine requiring the engine to be split in half for replacement. No one in town knew anything about these strange little cars with an air-cooled engine in the rear and the only person in town with metric tools was on vacation. All of us were aircraft mechanics and we decided we had a better chance of fixing the car than the locals. $10 rented us a small garage that repaired tractors and we had use of the space and limited tools for a night. After a couple of 6-packs of beer we had the engine out of the car with all the accessories removed. The problem of not having any metric tools became apparent when we tied to separate the engine to expose the damaged timing gear. There was no way to get a crescent wrench in between the cylinders to loosen the through bolts and we had to admit defeat. The car was sold to a local farmer with the engine and all the loose parts thrown in the back seat. We used just about every other means of transportation, including a TWA Constellation being ferried to Indianapolis, to make it the rest of the way to Indiana. Larry bought his cars cheap and never suffered a great loss when they finally had to be put to rest. One of his latter cars was a Dodge that required a firm grip on the steering wheel with both hands before putting on the brakes. There were no brake linings on one side and when they grabbed, it would snap that steering wheel out of your hands and take you into a ditch in an instant. We always figured this was better than into oncoming traffic.

We were now Cpl. E-4s, we knew our jobs, were 5 miles from the beach, drank beer whenever we wanted, and the top pastry cook of the Corps was in our mess hall. We were required crew on cross-country training flights to Phoenix, Tucson, Las Vegas, Reno, Sacramento, and San Francisco. Life was good, but due to change.

HMM-364 was scheduled to rotate overseas for a year starting in Nov/1963, which would place the two of us past our common discharge date of Sept. 7, 1964. This problem was solved by transferring us on February 14, 1963 to ride out our enlistment in HMH-462. It was a short walk to the 462 flight line located next to 364, but the difference in aircraft was large. The CH-37 was a leaking hydraulic monster with two R-2800 engines. Oil even ran out of these engines with them standing still. It had lead vibration dampers throughout the plane to help it from shaking itself to death and if you had a backfire on start up, you could count on changing 3-4 exhaust brackets. The crew chief would have to check all plugs on an oscilloscope before take off. It was so old and underpowered the fear of a cylinder not performing would keep it on the ground. Both Larry and I hated the CH-37 and found every excuse to sneak back to our old flight line helping our friends on a good aircraft. We never flew in the CH-37, always running away shaking our heads when asked if we would come along. Larry and I bunked together in the 462 barracks and were starting to feel pretty sorry for ourselves.

We fell into disfavor with the maintenance chief, MSgt. Omalak, almost immediately, as it was obvious we didn’t like his squadron or aircraft. We were not alone in our dislike for the maintenance chief. Even the squadron mascot didn’t like him and would growl as he strutted by. The good MSgt. reciprocated by putting me on group guard for a number of months and Larry found Marine Corps classes to attend. One of these classes was Embarkation School in San Diego. I asked Larry why he was taking this class and he said it got him away from Santa Ana and MSgt. Omalak. One of the jobs group guard had was controlling the opening and closing of the large blimp hanger doors. They were massive individual vertical sections that rolled on railroad tracks using considerable energy to operate. A lot of damage could be done if operated improperly, so group guard locked the switch. It was always a great day when MSgt. Omalak had to call and ask my permission to open the doors for his planes. A lot of times I was busy.

HMM-364 was still trying to fill their compliment of needed MOSs as they approached the overseas departure date. Everyone at HMM-364 knew of two excellent, but unhappy, candidates residing in HMH-462. A deal was cut through non-official channels if Larry and I would extend our enlistment 3 months, we would be taken back. We worked out all the extension papers at HMM-364 and then one-day, mysteriously, orders came to 462 for our transfer back to our old squadron. MSgt. Omalak was furious and we were on cloud nine. No one at 462 could figure out how we were able to pull it off as MSgt. Omalak controlled everyone by having everything go through him. He would have never let us out from under his thumb. Larry and I were already moved back in the 364 barrack the day the new orders hit and excited about starting another new adventure. The entry made in our service records for this transfer was October 9, 1963.

When we finally got to Okinawa our time was spent getting ready to ship out to Vietnam. We had to make sure everything was accounted for, packed properly, and staged for shipment. The supply lines in Vietnam at that time were very thin and we didn’t want to come up short at the start. I had been assigned by the supply officer to be in charge of an enlisted team to perform this task. I had become the Embarkation NCO. The job was terribly boring, repetitious, and a title no one seemed to want. Each shipping container was opened, the contents checked against a master, which was then checked off and initialed by the hierarchy. After more than a week of counting what seemed like thousands of tent pegs and the frustration of finding the right shipping containers, I wanted out of this job. Greasing rotor heads was a much better job. I finally went to the supply officer and asked why had he pulled me off an aircraft to do work out of my MOS. He said it was because I was the only person in the squadron to have actually gone through the embarkation and loading school in San Diego. He said the squadron was really quite lucky to have someone like myself in its ranks. I told him that he was partially right. The squadron was lucky to have someone school trained in this task, but it wasn’t me, it was Cpl. Larry Haupert. We went to S-1, checked the record books, and found that our friends in HMH-462 had made an entry error. Somehow I felt my friend MSgt. Omalak had reached out and got even. Now that the error was discovered, I figured my good friend Larry would be immediately called to take over. Instead, I heard we were almost done and it would be tough bringing Larry up to speed. I was told that it would be noted in my record book that, although I didn’t have the class, I did have the experience. I told them to just take it off my record and correctly enter it in Larry’s.

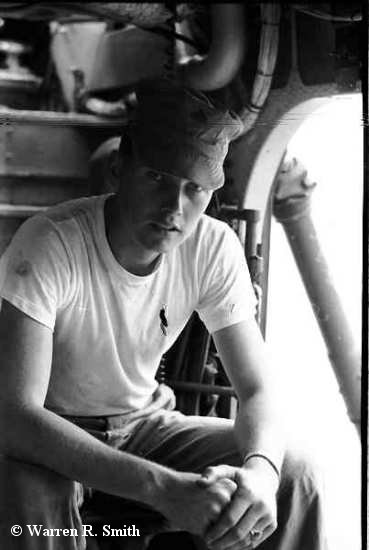

In Vietnam, we found ourselves coming and going much of the time without the luxury of a scheduled day. Missions were flown when needed and maintenance done in between. The crews on the planes became more of your day-to-day world as many times the days and nights flowed together on the flight line. Larry and I did take an R&R together to Bangkok, which brought back memories of our trip with the VW. This time we made it to our destination, but couldn’t get home. We always shared news from Indiana and any “care packages”. We lost weight together aboard the Valley Forge after pulling out of Subic Bay, without proper supplies, in reaction to the Bay of Tonkin Crisis. Larry still shares another experience from this time as I came close to cutting his little finger off in a mid-air tie between my survival knife and his hand. Larry still carries that scar with no feeling in the tip of his finger today.

We started making plans for our return to Indiana, as our discharge date got closer. I had purchased a 1964 Triumph TR-4 in Okinawa to be delivered to Long Beach, Ca. We would make that trip up Route 66 again, all the way this time, in much greater style.

Larry and I were returning to Futema from Hong Kong in November, when GySgt. Elliott met us on the runway asking if we could be ready for rotation Stateside in a couple of days. With Larry’s embarkation schooling and my previously acquired experience, we were ready to go the next day. The squadron had been extended a short time for an operation in Japan, which would have put Larry and I past our already extended enlistment. We had already extended once for the squadron and I guess it was decided the time had come to turn us loose.

It was sad to leave those we had shared so many close experiences and bonds. Close friends volunteered to handle shipping and paperwork that couldn’t be processed in time. Once again Larry and I were traveling on the same orders and similar entrees were being made in our record books. We flew via Flying Tigers Airline from Okinawa through Tokyo to Hawaii and on to Treasure Is in San Francisco. The stewardess looked outstanding in their high heels, tight jackets, and skirts. Larry and I almost said in concert the words sounded from behind the barbed wire at DaNang, when an Air Vietnam planes arrived carrying good looking passengers, “show time – show time”. We changed crews in Tokyo and as soon as we were airborne, the ladies that looked so good changed into wrap around dresses and slippers. This was the first clue it was going to be a long flight. We flew through the same night twice and caught up with the time we exchanged going over the date line on the USNS Breton a year prior. We had a 4-hour layover in Hawaii and it was a pleasant memory of our 9 months there in 1962. It was like we were backing our way out of the Marine Corps through our previous experiences. We had left Okinawa at 8:00 PM and arrived at Travis Air Force Base at 1:00 AM the following day on the calendar.

There was no slack at the Treasure Is. transient barracks. It was almost reminiscent of my experience at Iwakuni with questions of where are your barracks caps and what is this combat pay business? Larry and I had to pull flag duty of which we had never performed before and our names kept coming up on different rosters. The administrative machine dragged on for 3 days until we were discharged on November 19, 1964. Our enlistment day of May 10, 1960 seemed ages ago. We had combat aircrew wings and battle ribbons on our chest, discharge papers to take us anywhere we wanted to go in life, and our wallets were fat with back pay, unused leave, and travel pay. It was almost scary as we walked out the gate that last time to get on with our lives, but it was as we had started, we were still together.

Our first task was to head south to Long Beach and pick up the waiting red chariot that was going to be our transportation home. It was a great plan and it would make up for that bum trip in his 1954 VW Beatle a couple years ago. I could almost hear the cheers as we went through the small towns on Route 66. We caught a crowded commuter flight from San Francisco to LA to pick up the car at almost the same dock we left from to go overseas. We decided we were free to go anywhere we wanted with no defined schedule. For nostalgic reasons, we decided to make one last visit to Santa Ana where we had spent so many hours in previous years on liberty. Larry and I spent many hours playing ping-pong at a church run USO downtown eating home made cake and pie. We were in uniform and remarked how many blocks away we could spot Marines trying to masquerade as civilians. The young Marines from MCAF Santa Ana were impressed with what we carried on our chest, but we were already feeling out of place. We were out of the Marine Corps now and our futures awaited us back in Indiana. We drank in a lot of memories with a short walk around downtown Santa Ana and left without even trying to see our old base at MCAF.

The next day I inquired with the import company in Long Beach about picking up the car. It was time to move on. I was told there had been a shipping strike in England and the car was still on its way. It wouldn’t be there for another 3 weeks. Three weeks at this point seemed like an eternity and we both wanted to get home. When you have thought about it so much, through so many tough times, we just couldn’t hold back. We bought tickets out of LA to Chicago together and then on to Fort Wayne for Larry and Lafayette for me.

Larry and I shook hands in Chicago 4 ½ hours later, culminating 4 ½ years of sharing experiences to last each of us a lifetime. We felt older than our 22 years and also a little strange in this stateside environment we had left just a year ago. We didn’t know what the future held for us, but we had the confidence we could now handle most anything that came our way. We were proud to have been Marines and met the tests of performance under the stresses and responsibilities of combat operations. We even had that same slight smile on our faces as we saw young Marines hurrying through the airport on their way to their next assignments. It was that same smile the Marines we knew had when we were strutting around the summer before our “boot camp”.

Our record books closed and they could have just as

well filed them inside each other.

Similarities in the record books are as follows:

Birthdays 2 days apart

Point of enlistment and date the same

Service numbers 3 apart

Graduation from MCRD San Diego the same date and series

Completed ITR the same day and company

The same orders to aviation training

Graduated in the same class of helicopter maintenance

training

Same MOS number

Same orders to HMM-363

Same orders to HMM-364

Same rank

Secret Clearances

Same orders to HMH-462

Same orders back to HMM-364

Same orders on R&Rs

Same orders from Okinawa to Treasure Is. for discharge

Same service ribbons and awards

Same discharge point and date

Epilogue:

We have since both acquired our A&P licenses,

served in each other’s wedding, and have met with our families on a fairly

regular basis. Larry went on to become and still is chief pilot with Lincoln

Life Insurance. I graduated from Purdue University and worked for Dow Chemical

for almost 30 years. Larry and I are still friends and attended the last

HMM-364 reunion in Mesquite (2001) together. I am sure our common entries

will continue for many more years.

I probably don’t have to worry about Larry’s record

book causing me any more difficult assignments as they were burned up together

in the St. Louis Record Center fire.

Warren R. Smith has provided most of the history, in ready to publish form, for the Yankee Kilo Marines (Later known as the Purple Foxes) for the years 1962 through 1964. Had Warren not taken, and shared, his many photographs and spent untold hours preparing the narratives, I could not have published the glorious history of the HMM-364 Yankee Kilo Marines. These historical narratives are listed here:

Warren was the photographer for most of the Cruise Book photos taken during the 1964 deployment to Vietnam and other exotic Far East locations. He has shared those hundreds of photographs with the Yankee Kilo and/or Purple Foxes and all else who visit the site. The photo albums can be viewed here:

Again, I express sincere heartfelt appreciation on behalf of all who have served with the Yankee Kilo and/or Purple Foxes of HMM-364.

Franklin A. Gulledge, Jr., Major USMC (Ret)

Warren R. Smith's History Index

Back Browser or Home

-