R&R Reconnaissance, Someone Had to Volunteer!

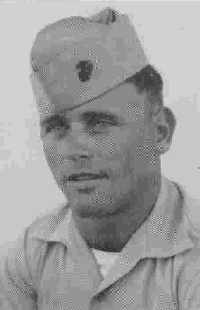

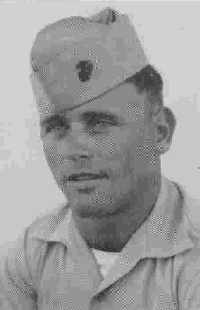

Cpl.

David Weber entered our squadron at the last moment due to a S-1 clerk

going on emergency leave. In fact, Cpl. Weber was on his way out

of the El Toro main gate to an administrative assignment with college recruiters

at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. It was a dream assignment,

to good to be true, that ended abruptly when he was stopped at the gate,

turned around, and given new orders to report to HMM-364 at MCAF, Santa

Ana. His luck went from bad to worse when he reported and found out

the squadron was leaving in 2 weeks for overseas. Cpl. Weber was

married with 3 young children and he had to work fast to change his plans

and take care of the needs of his family. This new assignment voided

all the previous accommodations. Being in an operational unit of

the Marine Corps is tough on those that are married and or have children

as there are very few foreign assignments in the Marine Corps that allow

dependents. In the wisdom of the old GySgt. that gave me advise on

the good and bad haircuts, “If the Marine Corps wanted you to have a wife,

they would have issued you one”. Cpl. Weber accepted his fate and

fell into the task of closing out his tour in Santa Ana. Dave had

gotten use to family moves as his dad was a career Navy photographer and

he had lived on various bases from southern Florida to Guam.

Cpl.

David Weber entered our squadron at the last moment due to a S-1 clerk

going on emergency leave. In fact, Cpl. Weber was on his way out

of the El Toro main gate to an administrative assignment with college recruiters

at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. It was a dream assignment,

to good to be true, that ended abruptly when he was stopped at the gate,

turned around, and given new orders to report to HMM-364 at MCAF, Santa

Ana. His luck went from bad to worse when he reported and found out

the squadron was leaving in 2 weeks for overseas. Cpl. Weber was

married with 3 young children and he had to work fast to change his plans

and take care of the needs of his family. This new assignment voided

all the previous accommodations. Being in an operational unit of

the Marine Corps is tough on those that are married and or have children

as there are very few foreign assignments in the Marine Corps that allow

dependents. In the wisdom of the old GySgt. that gave me advise on

the good and bad haircuts, “If the Marine Corps wanted you to have a wife,

they would have issued you one”. Cpl. Weber accepted his fate and

fell into the task of closing out his tour in Santa Ana. Dave had

gotten use to family moves as his dad was a career Navy photographer and

he had lived on various bases from southern Florida to Guam.

When we got to DaNang, Cpl. Weber was given the assignment

of Rest and Recuperation (R&R) NCO. He was to make sure everyone

went on an R&R somewhere and would make arrangements for them.

He was sort of the squadron travel agent. In performing this role,

he had to become familiar with the flight schedules of the various services,

their destinations, and ability to carry passengers. There was a

pretty steady stream of supplies coming into DaNang utilizing a lot of

transports without much going out in return. The trips were to Japan,

Okinawa, Manila, Hong Kong, or Bangkok. The aircraft varied from

Air Force C-119s and C-123s to Marine R4D and C-130s.

When

the squadron first got to DaNang everyone was fresh and excited to fly

missions for medals and money. The inbound supply flights were pretty

much on a regular schedule and Dave wasn't finding any takers for outbound

returns. His fear was that his allocation of seats would be reduced

which would hurt us in the future. Dave and I (Cpl.

Warren R. Smith) bunked together and he practically begged me to go

on a flight with him to fill some seats to Japan. I asked him what

we would do in Japan and he said that is what we had to investigate for

the squadron. The chopper I was assigned was lost the week before

we got to Vietnam and I had been waiting for its replacement to arrive

via the C-124. I had been filling in on flights and maintenance as

needed, so the time was right for me.

When

the squadron first got to DaNang everyone was fresh and excited to fly

missions for medals and money. The inbound supply flights were pretty

much on a regular schedule and Dave wasn't finding any takers for outbound

returns. His fear was that his allocation of seats would be reduced

which would hurt us in the future. Dave and I (Cpl.

Warren R. Smith) bunked together and he practically begged me to go

on a flight with him to fill some seats to Japan. I asked him what

we would do in Japan and he said that is what we had to investigate for

the squadron. The chopper I was assigned was lost the week before

we got to Vietnam and I had been waiting for its replacement to arrive

via the C-124. I had been filling in on flights and maintenance as

needed, so the time was right for me.

The first day of the recon mission, February 18th,

was a long one with an early wake up and a 6½ hour flight to Iwakuni,

Japan and stops in the Philippines and Okinawa along the way. I remember

we were in short sleeve summer uniforms and when I looked out the window

after landing at Iwakuni there were large piles of snow. We didn't

even have a jacket as snow was pretty far from our minds in DaNang.

We wanted to get closer to Tokyo as we figured there would be more to see

and do than where we were at in southern Japan. While at flight operations

we signed for a morning mail flight to Atsugi NAS. We were able to

get a bunk at the transient barracks, but had missed the evening meal at

the mess hall. We went to the EM Club for a sandwich and beer as

reward for our first day of “squadron work”. If you are on R&R

you should drink beer!

We had not even gotten our food order yet, when the

SSgt. that managed the club came to us and wanted to know why we were out

of uniform. We were wondering the same thing as we had been shivering

since arrival. We told him we had just flown in from DaNang where

it was hot and summer uniforms were the uniform of the day. We had

packed up all our wool dress uniforms when we left Okinawa to go to Vietnam

and they were still stored in a warehouse there. If we could have

gotten to them we sure would be enjoying their comfort at that time.

The guy didn't know anything about the operation in DaNang, couldn't understand

the whole concept of R&R and why we were on it, and his singular

focus was still that we were out of uniform. We were not getting

through to this ”keeper of the inn” and in frustration he left us with,

“ I am going to be keeping an eye on you two, so don't cause any trouble

or I will throw your sorry asses out in the real cold.” It sure felt

good to be a combat hero among your fellow Marines.

The next morning we couldn't leave Iwakuni fast enough

for Atsugi. We went straight for the special services department

when we arrive to find out what was happening in the area. They actually

had a number of different places with a variety of activities and discounts.

We were told a really nice package was skiing in the Japanese Alps and

we could check out all the equipment we needed right at special services.

It was now pay back time with Dave. I was born and grew up in Vermont

and learned to ski before I had gone to school. I convinced the guy

from Florida and the desert if he could water ski, he could snow ski.

Off we races to the PX and bought some sweaters, wind breakers, wool socks,

and gloves. We came back to special services and they fitted us with

boots, skis and poles. They also gave us detailed instructions in

the use of the train system and made reservations for us at a ski lodge

northwest of Tokyo.

The first shock we had as we proceeded down the track

on our first leg was that all the signs identifying the stops were in Japanese

symbols. Conductors that spoke English had little red tabs on their

badges and we weren't seeing any. We kept showing our tickets to

our conductor and he kept pointing at his watch. We would show and

he would point. We figured if we asked enough times he would remember

and see we got off at the correct stop. When we got to our first

stop and transfer point he came up and pointed at the correct time, which

was the time he had been showing us, nodded his head and pointed to the

platform. Our first lesson on the Japanese train system was that

it ran on an exact schedule you could set your watch by. We changed

at Yokohama and went into Ueno Station in Tokyo. It was bigger than

Grand Central Station in New York City and as you looked down from the

various levels there were rivers of humanity flowing constantly from all

parts of the station. Dave and I were a little overwhelmed, but with

some perseverance, found the track for the train going to the ski area.

We noticed clusters of people fairly evenly spaced along the track dock,

but stood back to watch and be polite. When the train pulled in,

on time, we found out why they remain on time. The doors only stay

open for a specified time and then they closed to be on their way.

If you were 30 seconds late for a train in Japan, you weren't even close.

The people had positioned themselves at spots right in front of the doors

and when the train stopped, the doors opened and the group started pushing

through this opening. I generally found the Japanese people very

courteous, but that didn't apply to this situation. This was the

last train tonight and we start to see if we didn't push forward we would

be left at the station. The flow through the door looked like of

funnel of people and I swung my parachute bag up into the apex of this

flow. The bag was pulled through the door with me holding onto the

handle. I looked back and saw that Dave was caught at the door.

He was carrying the skis and had caught the tip and tails on the outside

of the door. Everyone was pushing on Dave and he was centered on

the skis as they were bowing in. He finally was able to slid around

them and twist them enough to clear the door just as it slammed shut.

Once aboard we found another reason for the pushing and shoving, there

were more tickets sold than seats. We had to sit back to back in

the aisle on the parachute bag holding the poles and skies vertical.

The trip was festive with a lot of drink and song. The passengers

were made up mainly of young people on their way for a fun weekend.

Whenever the train stopped vendor would pass through the train selling

rice cakes, pastries, and tea. After about 2 hours we finally got

a seat and were able to relax. At least no one came by threatening

to throw us out in the cold. Our stop at the ski area was an easy

one as it was the end of the run and the train circles around and started

back for Tokyo.

At least our transportation to the Iwahara

Ski Lodge had its name on the vehicle in Japanese and English.

There were no roads to the lodge so we went cross-country in this

tracked vehicle up the side of the mountain. The people piled

inside and the baggage and skis were pulled in a sled tied on behind.

Dave and I were the last customers in that night for the lodge as it was

about 10:00 PM. The mama son met us at the door and immediately dispatched

someone to the kitchen to get us something to eat. She must have

had sons and knew how hungry we were. No sooner than food and drink

graced our table than another young American raced over to greet us.

He introduced himself as a Navy pilot off the Kitty Hawk visiting Yokohama

and he had been at the lodge since Monday as the only American. He

said if no “round eyes” had showed up by Saturday, he was leaving.

He talked non-stop for 2 hours without us getting a word in edgewise.

All those English words had dammed up inside of him and when he saw us,

they had to spill out. He said he had sat for hours in the evening

drinking beer and listening to the people sing Japanese songs having a

good time without him. It was apparent we had just become his best

friends. When our new best friend finally ran down, we all decided to call

it a night. Our rooms were little individual cubicles with a bunk

type bed, a small table, and chair. There was a fresh kimono and

shower shoes to wear to the public bath that covered most of the basement.

The meals were part of the package or you could order

special off the menu.

After breakfast, Dave found out that I lied about snow

skiing was like water skiing. He said for one thing, there was nothing

to hold on to and it hurt a lot more when you fell down. One time

I saw a crowd gathering around a big snow pile in front of the lodge.

When I got there a couple of guys were pulling on some legs attached to

skis. After quite an effort out of the pile Dave was pulled to a

grand applause. He said he got headed toward the lodge and didn't

know how to stop so he dove head first into the pile. He went in

so far that he could get back out until outside assistance was given.

Dave wasn't always sure what direction he was headed or where he would

end up. He stuck at it and by the second day he was doing a lot better.

Many times we would see Dave plodding down the mountain and each Japanese

he would come to would point further down the slope. He would lose

a ski and it would go forever till someone intercepted it. The Japanese

are so polite they would start apologizing before they would run into you.

When we were skiing with Dave the people behind us weren't sure which way

we would be going and neither did Dave. You would hear them yell

out “gomen nasai, gomen nasai” before they ran into you. Gomen nasai

means I'm sorry. There would be a lot of bowing and more gomen nasai

before all would be on their way.

Families we met would want to have their picture taken

with us and they used their kids as interpreters. The children in

Japan were required to take English in school. The people that were

leaving early would give us unused lift passes and everyone made us feel

right at home. There were some sweet young

ladies from Tokyo staying at the lodge that thought it was pretty special

to ski with some Americans their age. The guy on the left is David

Weber, then the LtJg. from the Kitty Hawk and then myself. The girls

were from Tokyo and were staying at our lodge. They reminded me of

little bunnies out there on the slopes and were good skiers. We had

a good time sharing our R&R with them and by this time Dave was starting

to at least look like a skier when having his picture taken.

The slopes were lighted and stayed open till 9 or 10

PM, which gave you all the skiing you wanted.

The basement house a large public bath and we would

sit in the warm water letting all the sore, tired muscles unwind from the

day. We sat for the longest time trying to talk to a group of Japanese

businessmen in the pool with us. We knew a little Japanese and they knew

no English. It took a long time, but every once in awhile we were

able to transmit a thought with the help of our few words and a lot of

sign language. When that happened all would slap the water with great

exuberance. I think we made a lot of friends because we tried to

be a part of their group and communicate with them on an equal basis.

I never thought at the time we would someday be watching the winter Olympics

from this same area.

We had beautiful clear days all the time we were there

and it was hard to think about going back. We were ringed by the Japanese

Alps and you could see the train come up the valley and make its loop

to head back to Tokyo. We were up so high that every thing was toy like

and make believe. Everything had a soft white crystal clean look.

This definitely was not DaNang. We felt confident we could recommend

this to anyone, even if they couldn't ski.

We skied into the 3rd day before we had to settle up

and leave for Atsugi. The total cost for the 3 days of room and board

was $18.00. I don't think that would buy a hamburger today.

We were veterans now, so the return trip was uneventful with the exception

we had real seats all the way back and Dave had learned how to get in the

doors with skis without hanging them up.

We even smarten up at the Iwakuni EM Club. We

wore or ski sweaters and pants and went unnoticed by our friendly “inn

keeper”.

When the back ramp lowered on the C-130, as we taxied

up to the HMM-364 area, the blast of dusty, hot air popped the bubble we

had been living in for the past few days. The workload was heavy

and our extra hands were folded back into the routine immediately.

On really hot, muggy, dirty days, if I tried real hard, I could transport

myself back to the top of that clean, crispy cool mountain in Japan.

I also knew sometime we would return to a better world where we would hear

behind us the words gomen nasai instead of a gunshot.

Submitted by:

Warren R. Smith, former Cpl. USMC

Back Browser or Home

x

Cpl.

David Weber entered our squadron at the last moment due to a S-1 clerk

going on emergency leave. In fact, Cpl. Weber was on his way out

of the El Toro main gate to an administrative assignment with college recruiters

at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. It was a dream assignment,

to good to be true, that ended abruptly when he was stopped at the gate,

turned around, and given new orders to report to HMM-364 at MCAF, Santa

Ana. His luck went from bad to worse when he reported and found out

the squadron was leaving in 2 weeks for overseas. Cpl. Weber was

married with 3 young children and he had to work fast to change his plans

and take care of the needs of his family. This new assignment voided

all the previous accommodations. Being in an operational unit of

the Marine Corps is tough on those that are married and or have children

as there are very few foreign assignments in the Marine Corps that allow

dependents. In the wisdom of the old GySgt. that gave me advise on

the good and bad haircuts, “If the Marine Corps wanted you to have a wife,

they would have issued you one”. Cpl. Weber accepted his fate and

fell into the task of closing out his tour in Santa Ana. Dave had

gotten use to family moves as his dad was a career Navy photographer and

he had lived on various bases from southern Florida to Guam.

Cpl.

David Weber entered our squadron at the last moment due to a S-1 clerk

going on emergency leave. In fact, Cpl. Weber was on his way out

of the El Toro main gate to an administrative assignment with college recruiters

at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. It was a dream assignment,

to good to be true, that ended abruptly when he was stopped at the gate,

turned around, and given new orders to report to HMM-364 at MCAF, Santa

Ana. His luck went from bad to worse when he reported and found out

the squadron was leaving in 2 weeks for overseas. Cpl. Weber was

married with 3 young children and he had to work fast to change his plans

and take care of the needs of his family. This new assignment voided

all the previous accommodations. Being in an operational unit of

the Marine Corps is tough on those that are married and or have children

as there are very few foreign assignments in the Marine Corps that allow

dependents. In the wisdom of the old GySgt. that gave me advise on

the good and bad haircuts, “If the Marine Corps wanted you to have a wife,

they would have issued you one”. Cpl. Weber accepted his fate and

fell into the task of closing out his tour in Santa Ana. Dave had

gotten use to family moves as his dad was a career Navy photographer and

he had lived on various bases from southern Florida to Guam.

When

the squadron first got to DaNang everyone was fresh and excited to fly

missions for medals and money. The inbound supply flights were pretty

much on a regular schedule and Dave wasn't finding any takers for outbound

returns. His fear was that his allocation of seats would be reduced

which would hurt us in the future. Dave and I

When

the squadron first got to DaNang everyone was fresh and excited to fly

missions for medals and money. The inbound supply flights were pretty

much on a regular schedule and Dave wasn't finding any takers for outbound

returns. His fear was that his allocation of seats would be reduced

which would hurt us in the future. Dave and I